|

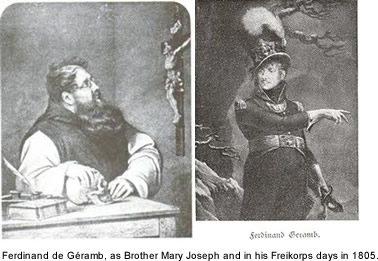

BioFile - The Curious Life and Adventures of Baron Ferdinand de Geramb

Ferdinand François, Baron de Géramb, more correctly Ferdinand Franz Freiherr von Géramb (1772-1848), was born in France to a father of Hungarian ancestry who had married into a silk-making family in Lyons. Although the elder Géramb did well, in 1790, shortly after the outbreak of the French Revolution, he took his family to Vienna. It’s not exactly clear what the younger Géramb did during the 1790s, though it seems likely that he soldiered, presumably for the Hapsburgs. It is known that in 1796 he married an Italian cousin, Theresa de Adda, with whom he had eight children before her death in 1808.

Following the 1802 Peace of Amiens, which temporarily ended the “French Wars”, Géramb reportedly had a duel in Vienna with a French hussar named Valabregue, due to some remarks Géramb had made critical of the French army. Tradition has it that Géramb was severely wounded, and both he and Valabregue narrowly avoided jail, since dueling was illegal. We also hear of Géramb working with French émigré groups, apparently promoting anti-Bonaparte conspiracies. Early in 1805 he helped raise 65,000 gulden to help fight a famine in a mountainous district. Later that year, with the outbreak of war, he was authorized to raise a volunteer freikorps which supported Austrian efforts during the Ulm and Austerlitz campaigns, a duty which he seems to have preformed ably. On August 21, 1806, by which time Géramb was a Chamberlain to Emperor Francis I of Austria, he received much popular acclaim for rescuing in somewhat spectacular fashion a workman who had fallen into the Danube at Pressburg. A year or so later he gained more popular attention by paying out of his own pocket for a monument to several fallen heroes of the recent wars.

With Napoleon’s invasion of the Hapsburg lands in the Spring of 1809, Géramb, by then a colonel in the Austrian Army, was authorized to raise a new freikorps to help defend Vienna. He reportedly requisitioned a splendid house, called upon young noblemen and wealthy bourgeois gentlemen to enlist, and quickly managed to commission 80 lieutenants, each of whom paid for the honor. For some weeks, as the ranks of his corps filled with volunteers, Géramb, a big handsome fellow with an elaborate moustache and light blue eyes, splendidly uniformed, frequented the cafes of the city with several equally magnificently outfitted aides-de-camp. Géramb’s freikorps performed some useful duties during the Spring and Summer, during the operations that culminated with the Battle Wagram (July 5-6). In the aftermath of the collapse of the Hapsburg forces and the end of the war, Géramb was granted the title “Freiherr – baron” by the Emperor Francis, but soon ran into some problems regarding accountability for the funds and supplies that he had requisitioned. The baron shortly left the country.

Not long afterwards the Baron turned up at Palermo, in Sicily. There he presented himself to Queen Maria Carolina of Naples and Sicily as having been sent by her nephew, the Emperor Francis, to perform whatever services were required. The handsome, charming, decorated war hero caught the queen’s eye. He was soon seen everywhere in her company, on carriage rides, picnics in the countryside, at the opera and the theatre, and so forth, while openly proposing wild schemes to overthrow or murder Napoleon, which may have tickled the queen’s fancy but had little chance of succeeding.

While in Palermo, Géramb had a quarrel with a British colonel, who issued a challenge. The Baron accepted, under condition that they have it out with pistols on the lip of the crater of Mt. Etna, with the winner having the option of dumping the loser, whether dead or merely wounded, into the fires below. Supposedly the duel actually took place, each man firing two shots: Géramb received a round through his hat, while the Briton’s elbow was shattered by the Baron’s second shot, whereupon Géramb chivalrously declined to toss the fellow into the crater. (As with many of the “details” of the Baron’s life, this duel is also reported as having taken place as a result of a quarrel that began in Vienna).

Géramb’s Sicilian idyll was short. His apparent closeness with the queen – perhaps they were having an affair? – shocked many people, and he left for Spain.

Landing at Cadiz in late January, 1810, the Baron promptly called upon the Austrian minister to the Spanish National Junta. He represented himself as having been sent by Hapsburg Chief Minister Klemens von Metternich for the purpose of raising a legion of volunteers and French deserters at his own expense to serve against Napoleon. Apparently the Junta gave him a commission as a general, plus a decoration or two, and, at his request, issued him a passport to go to England in order to raise funds and recruit volunteers.

Arriving in Britain in April, Géramb was surprised to find a rather unfriendly reception. While he did cut a swath through some respectable salons and gaming houses, word of some of the more questionable aspects of his life and career had already reached certain persons in government. So despite continual boasting of having “24,000 Croatians” ready to sail to Spain to fight against Napoleon, if only money was available, he made little headway toward obtaining a subsidy. Apparently in an effort to stimulate the government’s interest, he reportedly fabricated love letters from a British princess that he “leaked” to the press. Unimpressed, one day Lord Wellesley, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs (and brother to the Duke of Wellington), summoned the Baron to his office. Handing Géramb 100 guineas (today easily about £6,000), Wellesley gave him three weeks to leave the country. The Baron refused, tried to hang tough, even barricading himself into the house he was renting. Wellesley had the place stormed, arrested Géramb, and put him on a ship to Denmark, consigned to King Frederick VI, one of Napoleon’s staunchest allies.

Arriving in Denmark, the Baron, who had often published fiery diatribes against Bonaparte, was shortly sent by King Frederick to his good friend Napoleon. Géramb tried to con Napoleon into believing that he had seen the error of his ways, penning attacks on the “crimes of the English people” and even dredging up his “24,000 Croatians,” whom he now pledged to bring to Napoleon’s aid. But the Emperor would have none of it. Perhaps amused by the gift from his most determined enemies, Napoleon stashed the Baron in the fortress of Vincennes, where he remained until March, 1814, when the Allied occupation of Paris enabled a troop of Cossacks to liberate him and other political prisoners.

Until his incarceration by Napoleon, what is known about Géramb’s life is a mixture of the real, the rumored, and the fabricated, much of the fabrication having been done by the Baron himself. But his time in Napoleon’s fortress sparked a religious conversion. Soon after he was released from Imperial incarceration, Géramb entrusted his six surviving children to the care of his brother and the “protection” of Emperor Francis and Tsar Alexander and secured admission as a novice to the Trappist Abbey of Notre Dame du Port du Salut in central France, where he eventually became a model monk as Brother Mary Joseph. During the French Revolution of 1830, Brother Mary Joseph performed valuable services in defending his abbey from rioters. Soon afterwards, he undertook a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, about which he wrote a very detailed memoir which attained some popularity. Entering the service of the Holy See in 1833, his diligence and devotion brought him to the attention of Pope Gregory XVI, who appointed him an titular abbot and Procurator General of the Trappists. For the remainder of his life, Géramb wrote a number of important religious treatises and engaged in good works.

|